In 1402, a change in the course of the archipelago’s history commenced. After over a thousand years of indigenous rule and legends, Norman and Spanish explorers began to arrive on the coast of the archipelago with a single mission: to conquer the Canary Islands in the name of the Castilian crown. A turbulent era of just 94 years which forever marked the fate of two civilisations, testimony of which remains alive in several places around the geography of the islands.

For centuries, the warm, turquoise waters that bathe the Canary Islands were a distant mystery revealed only to the indigenous peoples who inhabited them. But in the 14th century, more and more navigators began to approach the archipelago. Some did so in error, others out of ambition. It was not long before they landed and discovered the huge wealth each island possessed. And this did not go unnoticed by the crown of Castile, either, who decided to step in with the aim of exploiting the tremendous strategic possibilities afforded by these volcanic lands in the waters of the Atlantic.

An archipelago featured in ancient myths and legends

There is no clear evidence of the presence of any civilisations other than the indigenous peoples before the arrival of the first explorers and conquistadors, but the Canary Islands were already known in ancient times. Ancient texts exist referring to them as the Fortunate Isles or the Hesperides. Others, like the Greek philosopher Plato, maintained that the archipelago was the remains of Atlantis. They believed it was located west of Gibraltar, and said the surface of the Canary Islands corresponded to the highest points, which survived the flooding of the legendary continent.

In those days, partly due to the precarious conditions of long voyages by boat, geographical knowledge was somewhat diffuse, and this helped to establish the idea that end of the world lay just beyond the Canary Islands, making the island of El Hierro the last land humans could tread on.

Lancelotto Malocello - the first conquistador or tourist?

The thirst for exploration of the age launched numerous navigators onto the seas. This was the case of the Vivaldi brothers, who set sail from the port of Genoa in 1291, towards the unknown. Their disappearance some time later led captain Lancelotto Malocello to set out in search of them. Following their trail, he passed between the hitherto-intricate Pillars of Hercules and eventually ended up landing in 1312 on the coast of the - as yet unexplored - island of Lanzarote, which was inhabited by the Majos, the indigenous islanders. Lancelotto Malocello decided to stay for 20 years, establishing himself as lord of the island and changing its original name (Tyterogaka) to one more in keeping with his person: Lanzarote.

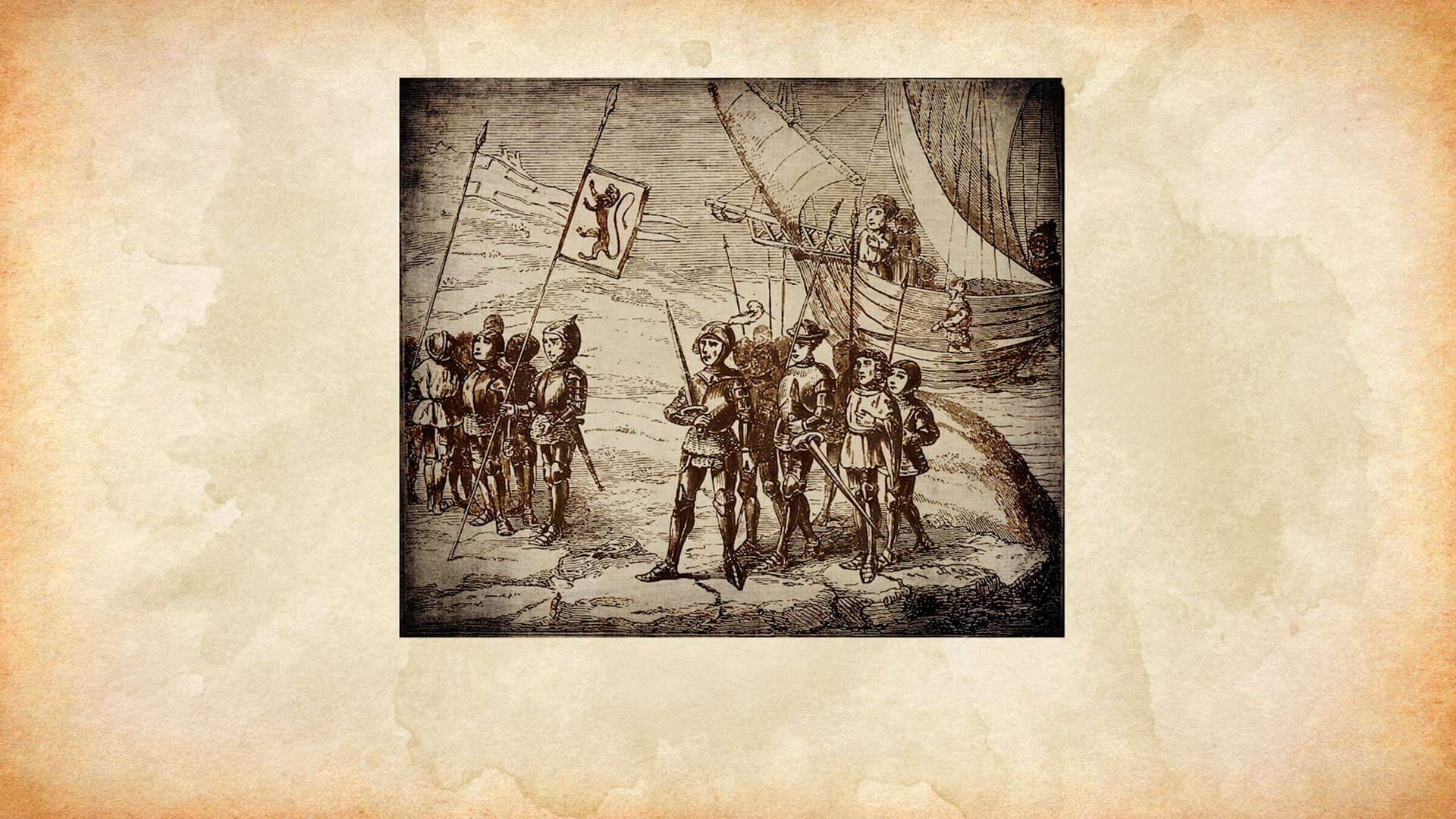

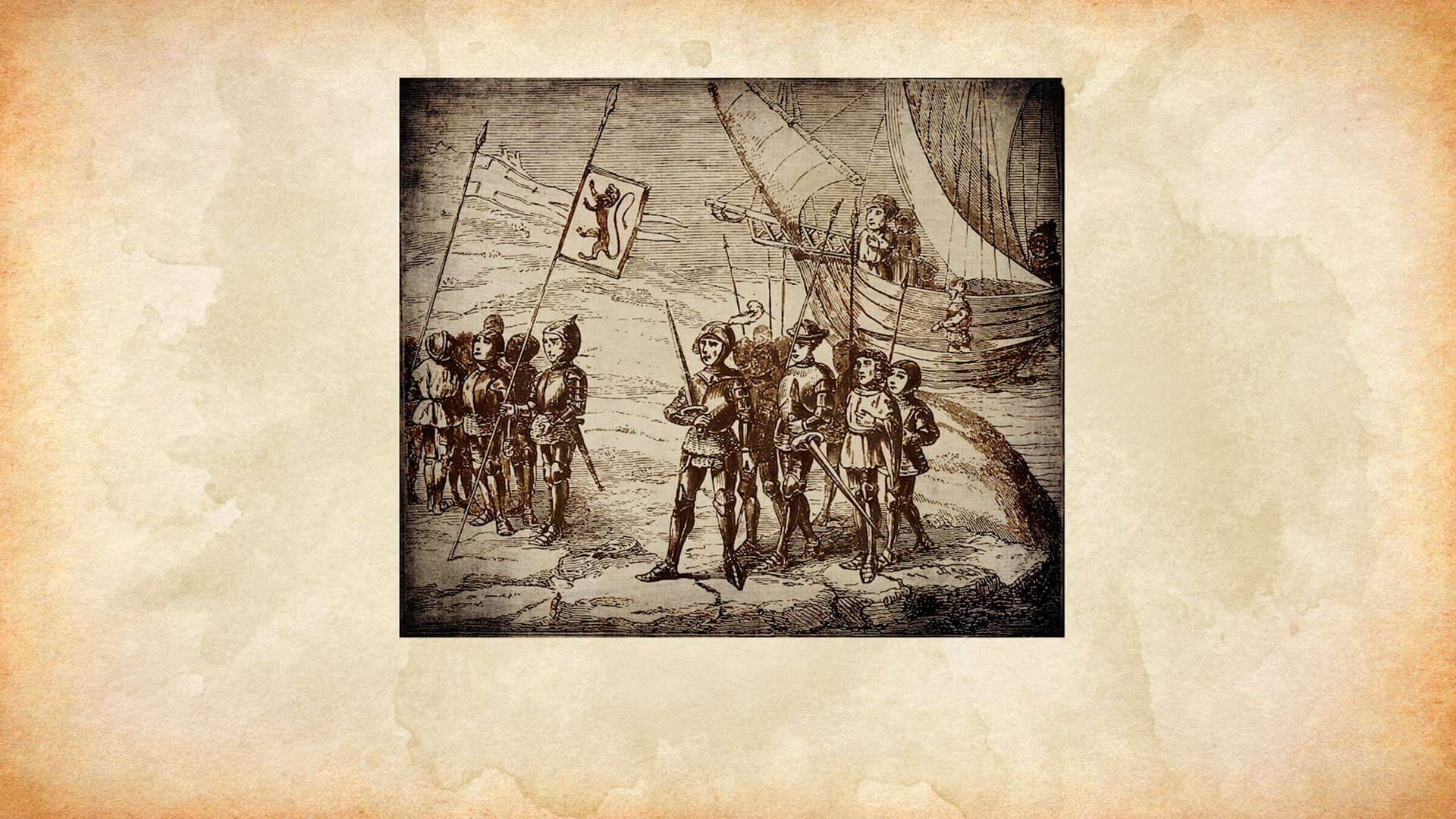

Jean de Béthencourt and the beginning of the ‘Conquista Señorial’ of the Canary Islands

Nearly a century after the arrival of Lancelotto Malocello, some other visitors anchored off the coast of Lanzarote. In 1402, the Norman lord Jean de Béthencourt disembarked with the French knight Gadifer de La Salle and his crew on the south of the island, in today's Papagayo. He offered the indigenous population a protection deal in exchange for the island, after which he built the ancient castle of Rubicón and a small chapel to honour Saint Martial.

His thirst for conquest guided his sails towards another island, El Hierro, where he barely met with any resistance on the part of the local population. With two islands already conquered, Jean de Béthencourt set course for Fuerteventura. Here, his arrival did not meet with such a good reception by many of the indigenous people, whom he had to fight and harass in order to take full control of the extensive ‘majorera’ island in 1405, just three years after his arrival. On it, he built the first town of the Canary Islands, and named it after himself: Betancuria.

The interest of the Normans

Contrary to appearances, Jean de Béthencourt had no military aspirations, but rather entrepreneurial designs. The Canary Islands are where orchilla grows, a lichen used in the past to dye clothes purple with natural substances. This colour, which was extremely popular in the clothes of the era, would make the textile factories Béthencourt owned in his homeland prosper.

To carry out his voyage - and at the same time monopolise the orchilla supply -, the Norman lord obtained the favour of King Henry III of Castile, “The Suffering”. In exchange, Jean de Béthencourt would have to organise the expedition, declare the land conquered to be the property of the Castilian crown, and run it as lord.

The Catholic Monarchs decide to take command of the conquest

After the swift work carried out by Béthencourt in Lanzarote, El Hierro and Fuerteventura, the ‘Conquista Señorial’ experienced a few quieter years. The lord Hernán Peraza, who had replaced the Normans, achieved a peaceful annexation of La Gomera. However, his continuous disrespectful behaviour and arbitrary actions against the population resulted in the Rebellion of the Gomeros, which took place at the tower of Torre del Conde during 1488.

Some years earlier, the crown of Castile had decided to undertake the conquest of Gran Canaria, La Palma and Tenerife, deemed the most dangerous islands due to the large numbers of indigenous peoples who inhabited them. In 1478 their troops disembarked on the beaches of La Isleta in Gran Canaria, initiating the ‘Conquista Realenga’. Here, they founded El Real de Las Palmas, the current historical centre of the capital and the place from where years of battles began, until they managed to take the final bastion of indigenous resistance, the Fortress of Ansite.

The next island to see the Castilian fleet was La Palma. The Benahoaritas used the island’s geography and lush foliage to defend themselves, but the conquistadors used trickery and deceit to capture Tanausú, the mencey who governed the impregnable area of Caldera de Taburiente, leading to the fall of the defences in the entire island.

The last island to be conquered, and the one that offered up the most resistance, was Tenerife. The crown of Castile gained control of it in 1496, with the founding of Realejos, but the Guanche resistance actually continued for years, under the insurgents.

The fate of the conquered

A large number of the indigenous Canarians were taken prisoner and used as slaves in the archipelago, on the Peninsula or on plantations on other Macaronesian islands. Another small number managed to survive in the more inaccessible areas of the interior of some islands, or were integrated into society after embracing Christianity. And although the traces of them were diluted, recent studies show that they are still present in the DNA of the local population.

In order to satisfy the growing demand for labour, the crown intensified its incursions into North Africa in search of slaves, bringing hundreds of Senegalese, Moors or ancient Guineans to the archipelago every year. These acts did not go unpunished, however. The Barbary pirates wreaked revenge with several attacks on the islands, causing King Philip II of Spain, “The Prudent”, to abolish the incursions.

Islands with much more to tell

The conquest of the Canary Islands is packed with stories waiting to be discovered through the old indigenous refuges in the midst of nature, the sunny beaches the conquistadors arrived at, and the entire legacy they left behind.

Although the story does not end there. The archipelago enables us to immerse ourselves in other eras, like that of the indigenous Canarians and their unique knowledge, or the heyday of commerce with the New World and the attacks by pirates that took place both on the coast and inland in the Canary Islands.