From famous naval battles to sports that had never been seen before in Spain. The British Empire has made a deep impression on the legacy and culture of the Canary Islands, and been one of the best ambassadors of local products such as wine. A history beginning in the 15th century and bristling with troubles, bitter pills and also sweet victories, of course.

England and the Canary Islands have been connected from long before aeroplanes linked the two destinations by just over four hours. The British influence in the archipelago goes back to the era of the conquest by Castile, with whom they had their ups and downs in the struggle to carve out a strategic position for themselves in terms of trade with the New World Since then, well-known privateers, scientists and merchants have left their mark on these sunny lands of volcanic origin.

Pirates with a British licence to attack

After being conquered, the Canary Islands quickly became the supply port for the expeditions that went back and forth from America, loaded with gold, silver, slaves, spices and seeds. This made the archipelago’s warm waters a favourite habitat for numerous pirates. Aware of this situation, the English decided to form an alliance with them in order to weaken other rival powers, in particular the crown of Castile. To do this they employed letters of marque, documents issued by the monarch which gave the holder permission to attack other countries or ships in the name of the English crown.

This was how pirates like Walter Raleigh, John Hawkins or the latter’s cousin, Francis Drake, became privateers, with their names written in the history of the Canary Islands. Drake, for example, commanded several fleets with the aim of causing the greatest possible amount of damage to the crown of Castile. In 1585, at the height of the war between England and Spain, he organised an attack to take the port of Santa Cruz de La Palma, but rough seas and the defensive artillery prevented him from doing so. Ten years later, in 1595, he made another attempt, in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, but the Canarian resistance thwarted his plan before he could land.

As well as La Palma and Gran Canaria, the English privateers also tried to take control of other islands in the archipelago. In October of 1740, Fuerteventura was subject to two nearly consecutive incursions. Both times the local population managed to emerge victorious after sheltering behind camels, enabling them to repel the first wave of enemy fire and counter-attack when the English were reloading their weapons. A feat that is re-enacted every year during the fiestas de San Miguel through a lively theatrical performance.

The arrival of the Royal Navy in Canarian waters

After years of defeats, the English decided to change tack and use a greater force: the Royal Navy. The decorated admiral Horatio Nelson set sail from British land with nine warships, 393 cannons, 3,700 soldiers and a single goal: to mount a surprise attack to take first the island of Tenerife first, and then the entire archipelago.

With a port defence of just 1,669 men and 91 cannons, it seemed Nelson’s plan would yield certain victory. However, the relief of Tenerife means it has numerous viewpoints which were used as lookout posts in that era. On the night of 21 to 22 July 1797, the islanders spotted Nelson in open waters, waiting for the right time to attack, from the surveillance post of Igueste de San Andrés. Thanks to a system of fire beacons and a rudimentary warning pole, the watchman was able to quickly warn the castle of San Cristóbal, where resistance began to be prepared under the command of General Antonio Gutiérrez.

With the surprise factor gone, after repelling several attempts to disembark by the British, the people of Tenerife managed to revert the situation. After numerous English casualties had been caused, and admiral Nelson had lost his right arm due to a cannonball, the Royal Navy surrendered, promising to never attack the Canary Islands again. This historic feat, known by the name of the Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, is still present today in the memory of all the islanders, thanks to the historical re-enactment of the Gesta of 25 July which takes place in Tenerife every year.

Wine and potatoes, the start of a phase with a much better flavour

In the Canarian ports of the 17th and 18th centuries, as well as battles, trade was also conducted... a lot of trade! An activity in which - quite contrary to appearances - the English also took an active part. Many of their ships sailing towards the Thirteen Colonies stopped over in the port of La Orotava (now Puerto de La Cruz) to take on supplies, especially wine. So much so that within a short space of time not only did they make the Canarian Malvasías the most-exported wines to England, but also, thanks to their commerce with America, they managed to secure a global monopoly over this beverage.

A century later, with the increase of other producers, wine exports declined somewhat. But this did not mean the end of trade, quite the contrary. The English carried out an annual exchange of potato seeds (papas) with the Canary Islands in order to keep the tubers healthy. This led to the potato crop boom in the archipelago, when British varieties like the King Edward, the Arran Banner or the Up to Date eventually adapted to the islands and the local gastronomy, being renamed as quinegua, arranbana and autodate.

Bananas and tomatoes bound for England

In the late 19th century, the presence of the English in the waters around the archipelago was more than conspicuous. In addition to global trade, the era saw the colonial expansion into Africa, leading them to take part in the construction of new docks in the ports of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and Santa Cruz de Tenerife. After they were completed, they were soon occupied by British shipping lines and coal stores, to provide support for the steamships that returned home. This context was exploited by Peter S. Reid, a British entrepreneur established in Tenerife who took advantage of the return journey of a steamship to freight the first shipment of bananas to England in 1878. Such was the reception they met with that in just five years, the number of boats used to transport this typical fruit had risen to 235, and by the end of the century this latter figure had been multiplied by ten.

Following the success reaped with wine, potatoes and bananas, the English decided to support the local agriculture, introducing new varieties of fruit and vegetables and improving farming techniques, fertilisers and the distribution of irrigation. A good example of this comes in the form of tomatoes, which were brought by the British in order to take advantage of the warm Canarian climate and the rich soil for the purpose of improving production before they were sent back to London or Liverpool. As a result of the number of boats arriving in the British capital from the Canary Islands, loaded with all kinds of produce, the old port area of the Thames became known as Canary Wharf, a name that still lives on today.

The first steps of tourism in the archipelago

The wealth of Canarian products, the sun, sea and constant trips by famous scientists and doctors began to draw an image of a healthy destination in the imagination of 19th-century Europeans. This idea penetrated in particular into the wealthier layers of English society, who began to occupy many of the first hotels on Tenerife and Gran Canaria.

Little by little, an increasing number of Britons began to arrive - and settle - in the Canary Islands, leading to the construction of new, modern facilities. This was how some of the places still here today came into being, such as the Queen Victoria hospital of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (commonly known as the Hospital Inglés, or English hospital), the Holy Trinity Church, the English cemetery or the Real Club de Golf de Las Palmas, which holds the honour of being Spain’s oldest golf club.

A source of inspiration for English scientists

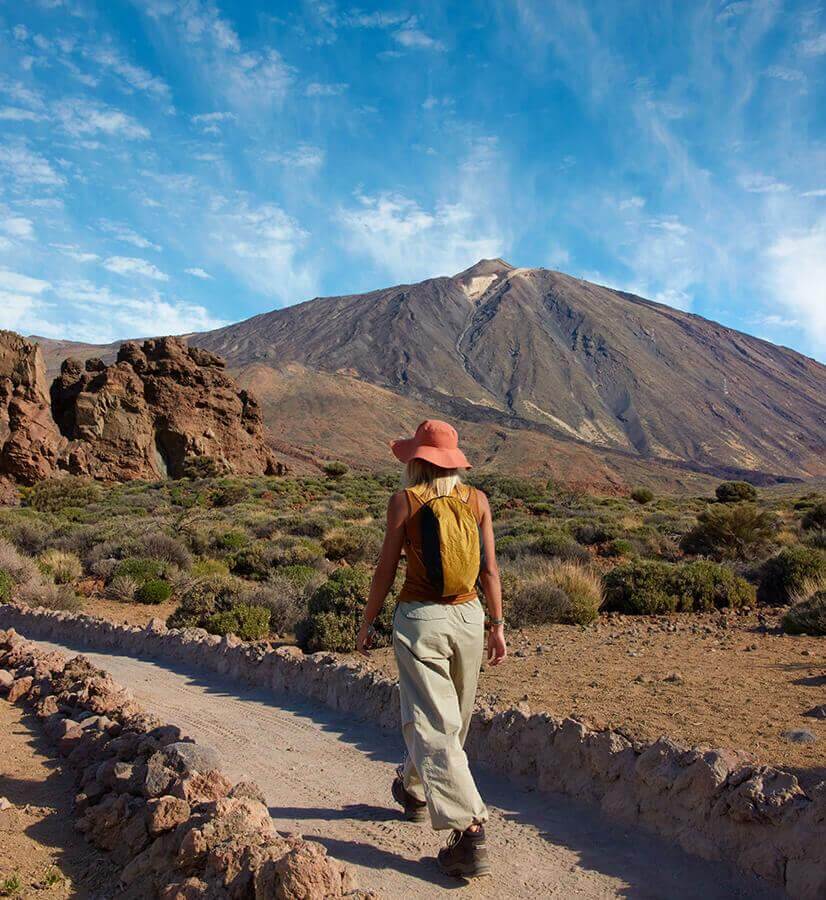

As occurred with the French scientific community, the peculiarities of the Canary Islands aroused the interest of British researchers. The altitude of the Teide, of the utmost importance for improving navigation in that era, was one of the first. In the 18th century, the Royal Society of London sent the doctor and naturalist Thomas Heberden to verify it, although he was by no means the only one. The father of modern geology, Charles Lyell, was drawn by the geological characteristics of the volcano, while others, like doctor Joseph Barcroft, used the surroundings to deepen knowledge of human breathing. The influx of British scientists to the Teide was such that there is a resting place at the altitude of 2,977 metres known as the Estancia de los Ingleses.

Others, however, preferred to penetrate ancient forests like those of the Garajonay National Park, to become the first to discover a unique nature. This is the case of the botanist David Bramwell, or the ornithologist David Bannerman, who visited the archipelago during the 20th century with the mission of studying Canarian flora and capturing different local birds for display in the British Museum, respectively.

An era written by women, too

The 19th and early 20th century are characterised by the appearance of the first female explorers. As a result of her determination, a pioneer like the English writer Olivia Stone was able to follow her adventurous spirit and become the first woman to explore the Canary Islands. A journey around the archipelago lasting several months which yielded “Tenerife and Its Six Satellites”, a 2-volume work with more than 800 pages in total which became one of the best travel guides of the day.

Islands with much more to tell

Ports, beaches, viewing platforms, forests, hospitals, golf courses… The deep impression England has left on the archipelago can be felt in numerous places on each island. An influence which, far from ending, continues to enrich Canarian life and culture today.

But it is not only the English who have left a great legacy in the Canary Islands. Other empires like the French also focussed their attention on an archipelago which for centuries was the land of surprisingly knowledgeable indigenous peoples.