In their stark realistic portrayal of Spanish society of the nineteenth century, his highly regarded novels are considered comparable to Honoré de Balzac and Charles Dickens. Widely read and translated into numerous languages, his work offers a glimpse into nineteenth century Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, in Galdós’ time already a bustling international port.

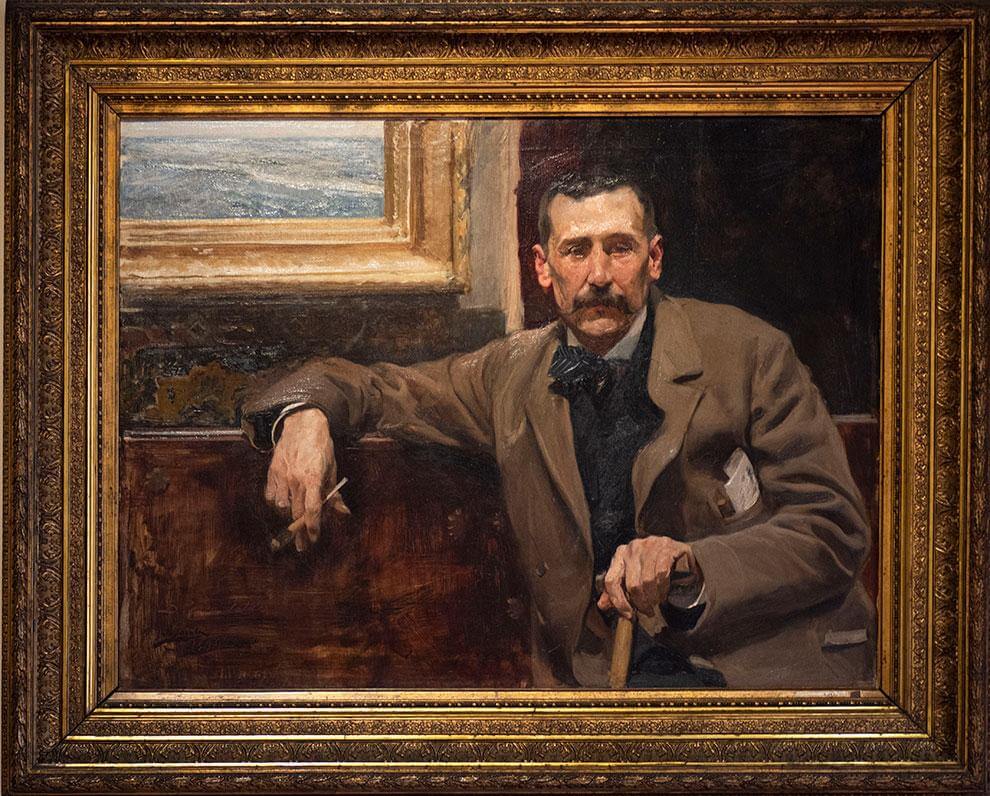

Benito Pérez Galdós was born on the tenth of May 1843 in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (the Canary Islands). He died on the fourth of January 1920 in Madrid. To coincide with the centenary of his death, the life of the writer will be celebrated in the Canary Islands throughout 2020. He is considered Spain’s greatest novelist since Miguel de Cervantes. [Galdós wrote] “seventy-seven novels, twenty-three short stories and twenty-three plays as well as newspaper articles and essays,” says Yolanda Arencibia, a professor at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. “He created universal characters. This is revealed in his women who stand out. They are faced with a deep rooted and moving struggle to escape from the prison in which Galdós realised that they lived in his time.”

Las Palmas de Gran Canaria through Galdós’ eyes

Arencibia affirms that Galdós’ background coming from an island affected his vision of Spain. “When Galdós arrived in Madrid his curiosity is typical of a native islander,” says the professor. “There isn’t a madrileño writer of his era that is interested in the history of Spain like he is. This is because the Gran Canaria of his youth was Spanish, but it was also trading with English, French, Italian, American and African merchants. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria was a first class international port.”

Galdós spent his youth walking the streets of the Vegueta neighborhood of Gran Canaria. “He went to the beach in Triana. He travelled across the Puente de Palo which crossed the Guiniguada ravine, and when he left his school in San Agustín he went to visit his classmates’ houses. Friends included the Wangüemert family. He performed plays. He chatted,” says Arencibia.

Traces of all these experiences can be found in Galdós’ work. “He kept looking at the market stalls. He went to the Cathedral, the Plaza Cairasco and the Gabinete Literario (which was then the headquarters of the Royal Philharmonic Society). He loved music and went on many processions.” From a young age he had a notepad with him. “He was very shy and introverted. By stepping on old cobblestones which lined the islands’ streets his character was forged. He had curiosity and sarcasm, that form of humour so common in the Canary Islands which makes fun of what’s in front of us.”

Canarian in appetite and mind

In Galdós' pantry in Madrid there were products from his island home: gofio (ground and roasted cereal), cheese, wrinkled potatoes, sauce and all the necessary ingredients to make ribs with pineapple, corn on the cob and stew. He loved sweet things such as trout (dumplings normally stuffed with sweet Christmas potatoes) and rapadura (an unrefined whole cane sugar made from cane honey, Canarian flour, sugar, cinnamon, almonds and lemon).

"We must bear in mind that he had to travel to the Canary Islands by boat from Cádiz, and he often became sea sick," says Teo Mesa (a writer who has examined Galdós’ work as a painter and has authored books such as ‘Galdós. Plastic Artist’ and ‘Art Inspired by Galdós ’). Yolanda Arencibia says: “this is why he only returned to the Islands three or four times but nonetheless made sure that his family regularly brought him products from their farm in La Aldea or from their summer house in Santa Brígida” [both in Gran Canaria)].

Later in life Galdós travelled to France, Britain, Italy and Portugal, places which allowed him to combine his Canarian mindset with the naturalistic literary currents swirling around Europe. He could portray characters so sensitively because he had learnt about the world and the reality of the street. He moved about “without fear of wearing out his shoes, much less fearing to tell the truth about what he saw. This was what made his work influential,” says Yolanda Arencibia.